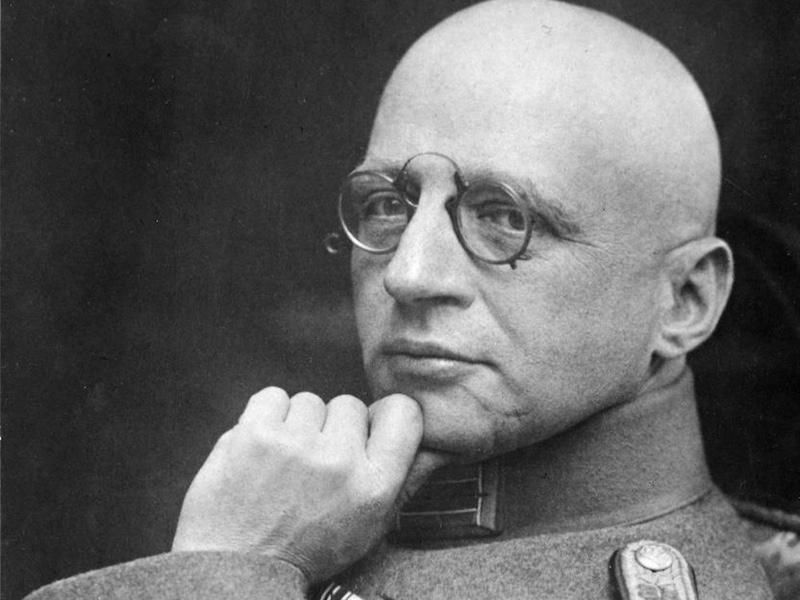

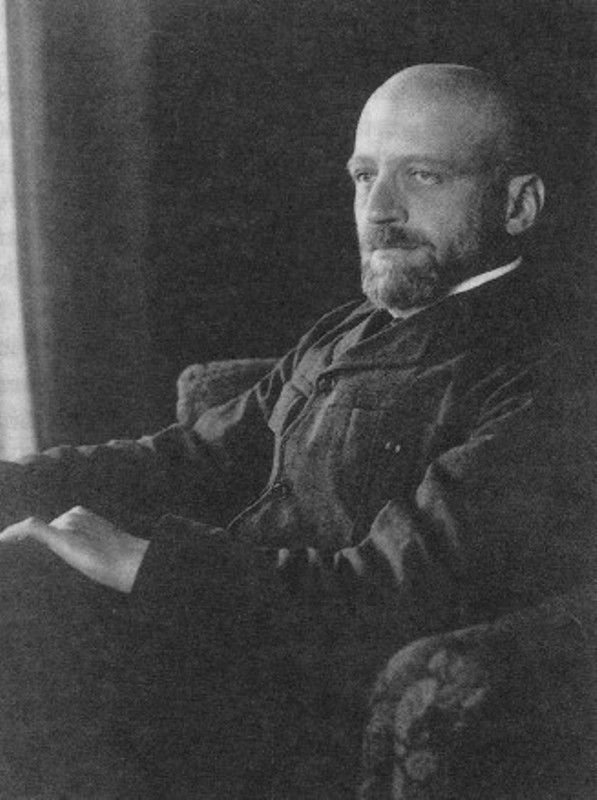

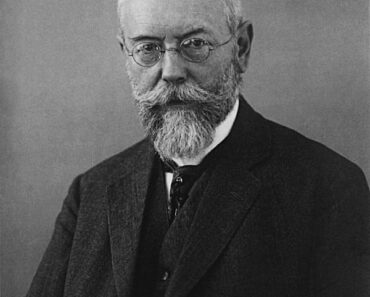

Fritz Haber (1868-1934) was a German chemist known for the invention of the Haber-Bosch process for which he received a Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1918. He is also considered the father of Chemical Warfare. He died on 29 January 1934 in Basel, Switzerland.

Wiki/Biography

Fritz Haber was born on Wednesday, 9 December 1868 (age 65 years; at the time of death) in Breslau, Prussia. His Zodiac sign is Sagittarius.

Fritz Haber completed his primary education at the Johanneum School which was equally welcoming to Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish students. He attended St. Elizabeth classical school affiliated with the largest protestant church in Breslau, St. Elisabeth’s at the age of 11. He finished his education at St. Elizabeth classical school on 29 September 1886, and later, joined Berlin’s Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (commonly known as the University of Berlin) to study chemistry and physics. After completing one semester at the University of Berlin, he joined the University of Heidelberg in 1887, where he attended the classes of Robert Wilhelm Bunsen. Later, he returned to Breslau, to complete the compulsory military service, where he spent one year in the Sixth Field Artillery Regiment. In 1890, he attended the Technische Hochschule of Charlottenburg in Berlin, the largest engineering college in Germany to study chemical technology under Carl Liebermann. He also teamed up with Liebermann on a project related to indigo. He received his doctorate from the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität for writing a thesis on Über einige Derivate des Piperonal (About some derivatives of Piperonal) under A.W. Hoffman on 29 May 1891. In 1892, he joined Eudgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich, as a post-doctoral student to study under Professor George Lunge for one semester.

Family

Fritz Haber belonged to a German Jewish family.

Parents & Siblings

Fritz Haber’s father, Siegfried Haber (1841-1920), was a wealthy merchant and a city councillor who ran the business of dye pigments, paints, linseed oil, whale oil, resins and pharmaceuticals.

His mother’s name is Paula Haber (1844-1868), who was Siegfried’s first cousin. Paula Haber died three weeks after giving birth to Fritz, at the age of 24.

Later, Siegfried got married to Hedwig Hamburger, in 1874. Fritz Haber had three stepsisters named Else Caroline Freyhahn, Helene Weigert, and Frieda Glücksmann.

Wife & Children

Fritz Haber got married to Clara Haber, nee Immerwahr (1817-1915), the first woman to receive a doctorate in physical chemistry from the University of Breslau in Germany, on 3 August 1901. The couple had a son, Hermann Richard Haber on 1 June 1902. On 2 May 1915, Clara Haber shot herself with Fritz’s pistol, in the garden of their house, reportedly because of various reasons such as a dysfunctional marriage, disagreements about Fritz’s involvement in the German war, her husband’s affair with another woman named Charlotte, and depression. In 1909, while expressing her disappointment, she wrote to her PhD adviser and confidant, Richard Abegg, the following lines:

What Fritz has gained during these last eight years, I have lost, and what’s left of me, fills me with the deepest dissatisfaction.”

On 25 October 1917, Fritz Haber got married to Charlotte Nathan, who worked as a manager of the club “Deutsche Gesellschaft 1914,” at the time. The couple had a daughter, Eva Lewis (1918-2015), and a son, Ludwig Fritz (Lutz) Haber (1921-2004). The couple got divorced on 6 December 1927 due to an unhappy marriage.

Other Relatives

His great-grandfather, Pinkus Selig Haber, was a wool dealer from Kempen (now Kępno, Poland). His great-grandmother’s name is Louise Haber. His grandfather’s name is Jacob Haber (1807-1846) and his grandmother’s name is Caroline Haber (1811-1866).

Relationships/Affairs

Fritz Haber dated Clara Immerwahr for a brief period when they met at a dancing lesson. Clara declined Fritz’s offer of marriage because she wanted to be financially independent. In April 1901, they met again at the annual conference of the German Electrochemical Society in Freiburg and the affair rekindled. Reportedly it was Clara’s PhD adviser and the friend of Fritz, Richard Abegg, who encouraged the affair. On the occasion of their engagement, Fritz Haber professed that,

He was in love with his bride (Clara Immerwahr)as a high‐school student” and during the intervening years, he had “honestly but unsuccessfully” tried to forget her.”

He reportedly had an affair with another woman named Charlotte Nathan, while being married to Clara Immerwahr. ((National Library of Medicine))

Religion/Religious Views

Fritz Haber was born into a Hasidic Jewish family but never practised his religion. Later, he converted from Judaism to Lutheranism as a student in Jena in 1893. ((BBC))

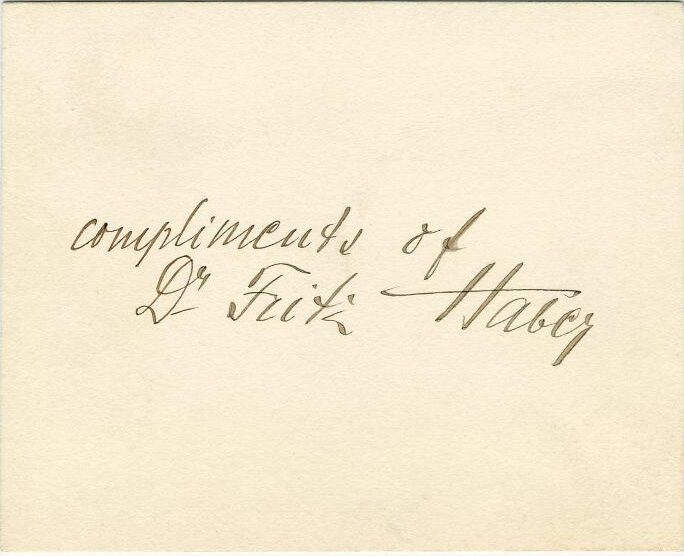

Signature/Autograph

Career

Apprenticeship

After graduation in 1891, Fritz Haber returned to work in his father’s company, in Breslau but that didn’t go as planned because of the friction in their relationship. After that, he got his first job at Leipziger Distillery in Budapest, with the help of his father, Siegfried’s business connections. Later, he joined an Austrian fertilizer factory near Auschwitz in Galicia and then, Feldmühle Paper and Cellulose Works; he worked as an unpaid junior clerk in all three places. In 1892, he returned to Breslau again and joined his father’s organisation. During this time, Fritz suggested that the cholera epidemic would spread and convinced his father to buy large quantities of calcium hypochlorite, the only treatment for cholera at the time. His suggestion was proved wrong when the epidemic was isolated and the Habers were left with big stocks of calcium hypochlorite. This incident developed a strain in their relationship, and Siegfried advised Fritz to return to studies as he realised his son was not meant for business.

Academic Career

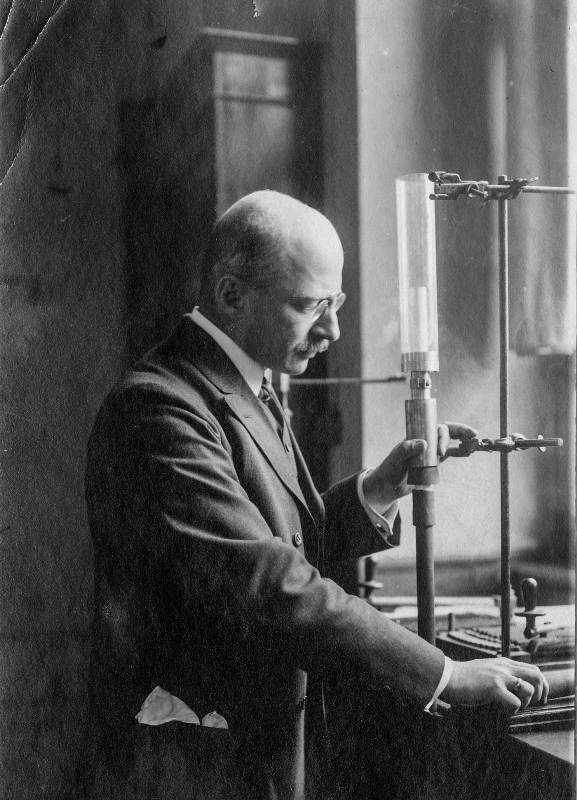

In 1892, Fritz Haber joined the University of Jena as an assistant to Ludwig Knorr. In hopes of getting a better academic position and avoiding anti-semitism, Fritz converted to protestant-Christian faith on 16 December 1894. After spending one and a half years in Jena, he moved to the Technical University of Karlsruhe to work as an unpaid assistant to Professor Hans Bunte. During his time at Karlsruhe, he worked on various problems such as the thermal decomposition of hydrocarbons, dye technology, gas technology, electrochemistry, thermodynamics of the reactions of solids, metal corrosion, and the thermodynamics of gas reactions. His work on the thermal decomposition of hydrocarbons became his habilitation thesis and he was appointed as privatdozent Technical University of Karlsruhe in 1896. Further, he published the book, Grundriss der Technischen Elektrochemie auf theoretischer Gundlage (Outline of technical electrochemistry on a theoretical basis) which resulted in his promotion to the honorary title of außerordentlicher (extraordinary) Professor in technical electrochemistry by order of the Grand Duke Friedrich von Baden on 6 December 1898. He worked on many research projects such as the iron plates used in printing the bank notes, and the corrosion of underground gas pipes due to stray currents emitted by current used for operating streetcars. In 1904, he started working on the catalytic formation of ammonia. He published his second book, Thermodynamik Technische Gasreaktionen (Thermodynamics of Technical Gas Reactions) in 1905. In 1906, Fritz Haber was offered the position of full professor and the director of the electrochemistry institute at the Technical University of Karlsruhe which he accepted.

The synthesis of Ammonia ‘Bread from air’

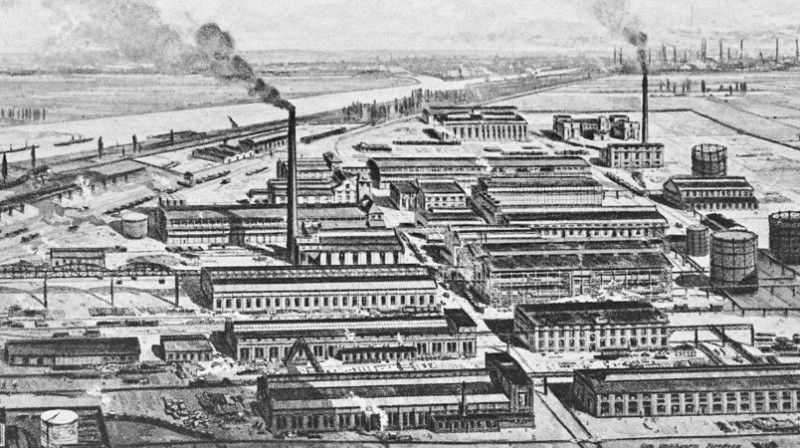

From 1894 to 1911, Fritz Haber worked on the catalytic formation of ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen in high temperatures and pressure with his assistant Robert Le Rossignol. After their continued efforts they found that uranium and osmium were better catalysts for ammonia synthesis than iron and managed to synthesize ammonia. Fritz Haber filed a patent for ammonia synthesis in 1908 and received it in 1910. In July 1909, BASF (Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik) started the search for the ideal catalyst for synthesis and charged Carl Bosch, who was a chemist and an engineer as the head of the project. Eventually, Carl Bosch found a better replacement for the catalyst used for the reaction. This procedure was known as the Haber-Bosch process and is still heavily used in producing ammonia. Fritz Haber partnered with BASF (Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik) for large-scale production of ammonia and BASF started to build an ammonia synthesis plant in Oppau, Germany, in 1910. The Oppau plant started its operation in 1913.

Fritz Haber’s ammonia synthesis solved the problem of the nitrogen shortage which directly impacted Chile’s nitrogen industry, making Germany the producer of one-third of the fertiliser nitrogen in 1913. He received a Nobel Prize in chemistry for his work in 1918. Many prominent chemists including Nernst, Ostwald, and Emil Fischer, wanted to develop an institute dedicated to research in chemistry. The construction of one of the institutes, Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry was funded by the entrepreneur Leopold Koppel, who provided funds with a condition of Fritz Haber to be made the first director. The inauguration of the institute happened in 1912 in Dahlem, Berlin and Fritz Haber accepted the offer.

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry with the director’s (Fritz Haber) mansion (in the right), 1912

The Great War ‘Gunpowder from Air’

After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Fritz Haber signed the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three and joined the 92 other German intellectuals. His invention of synthetic ammonia replaced Salpeter (the base material for explosives) which was hard to import during the war. He developed chemical weapons for the German troops when the military was looking for new weapon technologies. He proposed the first poison gas attack that was used in the Battle of Ypres by releasing chlorine gas onto the military allied soldiers in Belgium, on 22 April 1915. He was promoted to the rank of captain, after the success of the chlorine cloud attack that he celebrated at his mansion in Dahlem on 1 May 1915. Haber-developed gas masks with three-layer filters which helped against gas attacks. Later, the development of mustard gas and phosgene happened at Haber’s Institute which was used in the war in 1917. Eventually, gases proved to be a weak weapon. In 1919, Germany also started a secret program under Fritz Haber for the development of chemical weapons despite the Versailles treaty that banned Germany from owning lethal weapons. He was declared a war criminal when the list of nearly 900 names was published on 3 February 1920. He grew a beard and fled to Switzerland with his family to protect himself.

The charges were dropped and he returned to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. He worked on projects like “Gold from Seawater” and many others between 1920-1926.

The end of his career

On 30 January 1933, Hitler came into power which marked the rise of national socialism. When the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed on 7 April 1933, Fritz Haber was forced to dismiss all twelve of his coworkers of Jewish ancestry. He resigned from the position of the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on 30 April 1933. He left Germany on 3 August 1933. He joined the University of Cambridge in England for a position arranged by Sir William Pope. Later, he was offered the position of director at the Sieff Research Institute in Rehovot, in Mandatory Palestine, but he was not able to assume this position as he died of heart failure, mid-journey to Palestine.

Awards, Honours, Achievements

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1918)

- Bunsen Medal of the Bunsen Society of Berlin (1918)

- Wilhelm Exner Medal (1929)

- Rumford Medal, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1932)

- Goethe-Medaille für Kunst und Wissenschaft (Goethe Medal for Art and Science) from the President of Germany

- He was a member of various scientific associations such as the German Academy of Natural Sciences Leopoldina (1926), Société Chimique de France, Chemical Society of England (1931), and Society of Chemical Industry, London (1931).

- In 1932, he became an honorary Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Soviet Union.

- Fritz Haber received honorary doctorate degrees from various universities such as Gottingen University, the University of Wittenberg, and the Karlsruhe Engineering College.

Legacy

- The Institute for Physical and Electrochemistry at Berlin-Dahlem was renamed the Fritz Haber Institute after his death.

- The Minerva Foundation of the Max Planck Society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem developed the Fritz Haber Research Center for Molecular Dynamics in 1981.

- The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Dahlem was renamed Fritz Haber Institute in 1953.

- The private collection of Fritz Haber exists at the library of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot in his honour.

Death

He had been suffering from angina pectoris for a long time. Fritz Haber died of a heart attack in Basel, Switzerland, while travelling to Palestine on 29 January 1937, at the age of 65 years. He was cremated and buried in Basel’s Hörnli Cemetery on 29 September 1934. His first wife, Clara Haber’s remains were buried with him in accordance to his wish.

Facts/Trivia

- Fritz conducted his early chemistry experiments at his Uncle’s apartment, Hermann, a liberal who ran a local newspaper, where he generously offered him space. He always had a keen interest in chemistry and used to perform chemical experiments even as a schoolboy.

- Fritz Haber’s father wanted him to pursue commercial education and join the family business but he went against his father’s wishes and decided to study physics and chemistry in 1866.

- In 1891, Fritz Haber hardly passed his oral examination for his doctorate, when he presented his work to a board of examiners including Hoffman, Karl Rammelsberg, August Kundt, and Wilhelm Dilthey. In the report, the examiners mentioned that he was ignorant of the resistance measurements of electrolytes but he was appreciated for his general thoughts.

- Many members of Fritz Haber’s extended family died in the concentration camps operated under Nazi law in Germany.

- Fritz Haber’s youngest son, Ludwig was an eminent economist and historian of chemical warfare in World War I and he published a book “The Poisonous Cloud” on 20 February 1986.

- The first patent filed by Fritz Haber was for a technique of staining cotton and other fibres with chromium.

- For his contributions to the German industry in 1913, he was given the Order of the Crown Third Class and an autographed portrait of Wilhelm II.

- Fritz Haber and Albert Einstein grew a close friendship when Einstein was called for a professorship at the Prussian Academy of Science in Berlin in 1914. After Fritz’s death his friend, Albert Einstein said in his eulogy,

Haber’s life was the tragedy of the German Jew, the tragedy of unrequited love.”

- After the dismissal of his Jewish coworkers from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in 1933 under Nazi law, Haber decided to find jobs for them abroad for which he sought the help of Albert Einstein. Einstein replied to Haber in one of his letters and said,

I can imagine your inner conflicts. It is similar to having to give up a theory that one has worked on all one’s life.”

- A former British student of Fritz Haber, J. E. Coates, was invited to give a memorial lecture at the Chemical Society of London in 1939.

- Several plays and short films have depicted Fritz Haber’s life such as Einstein’s Gift (2003), The Greater Good (2008) and, Haber (2008).